Each city has its unique challenges, political culture, and history that candidates must be aware of and adapt to in order to become successful in these respective areas.

Charleston, South Carolina, with its prominence in racial issues in recent headlines and its past, is no exception. While Mr. Sanders has minimal chances of winning the allegiance of the vast majority of white residents of this city aside from the minority of far left elements due to the tendency of most local whites toward either conservative or mainstream Democratic politics, there are certain factors that Mr. Sanders must also consider if he is to win the allegiance of the city’s black voters.

The Factor of History

Charleston’s black history runs deeper than that of most American cities. The first Africans arrived here in 1670 aboard the ship “Three Brothers” along with Captain Nathaniel Sayle, which, according to historian Peter Wood in his book ‘Black Majority,” began a process that led to the black population actually outnumbering the whites in this area from the 1700s to the Great Migration to Northern cities in the 1920s. This surplus was due to the demand for slave labor in the local rice fields. There were two important results of this population dominance; the black population in Charleston maintained more of their African speech patterns and cultural practices than almost any other black community in America in what is called the Gullah culture (alternately called Geechee) whose names are said to be inspired by the Gola and Gizze tribes of Sierra Leone and Liberia of which most Charleston blacks are descended. This community, which has traditionally consisted mostly of the city’s black poor and working classes, faces problems of displacement and cultural issues typical of indigenous populations that will be discussed later in this essay. Another result of the dominance in population was the greater risk of slave rebellions. The best known of these were the attempted rebellion by Denmark Vesey and his followers in 1822, and the Stono Ferry rebellion of 1739. Each of these resulted in the execution of its plotters and greater restrictions upon the black population.

During Reconstruction, the black community temporarily prospered in the rise of black political power, as African Americans served as Lieutenant Governors, college professors, city councilmen, policemen, and other prominent positions. With the fall of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow laws and disfranchisement at the close of the 1800s, a sense of bitterness and futility settled in, but occasional advancements took place. Among these was the 1898 meeting against lynching at Mother Emanuel AME Church, the rise of black schools and local businesses, and armed resistance during the 1919 race riots. Unfortunately, the best and brightest of the black population was led by the lack of opportunities to migrate to cities such as New York City, Washington DC, and Philadelphia, while the local masses remained largely stagnant.

However, in the 1950s and 60s, local leaders such as businessman Esau Jenkins, educator Septima Clark, mortician Herbert Fielding, and several others led the local civil rights movement. Dr. Martin Luther King occasionally visited these leaders and spoke in this city, inspiring considerable change in regard to segregation and political restrictions, reaching its peak during a hospital strike of black workers in 1969. Local radio station WPAL also mixed programs of political information with Soul and Gospel music. However, with the deaths of these leaders and the fall of WPAL by the beginning of the millennium, apathy and despair again set in. While the city of Charleston prospered under its leadership, a major side effect was the gentrification of Charleston and the displacement of its poor black population and the decline of its traditionally black schools.

The Walter Scott and Mother Emanuel killings

Two events in the first half of 2015 brought national attention to the problems of black Charlestonians. The North Charleston police department was infamous in its reputation in dealing with its black citizens. Many blacks have complained of frequent stops by the police of that section, and it was not uncommon for local blacks to warn others about driving or walking in North Charleston. On April 4, 2015, 50 year old Walter Scott ran from Officer Michael Slager at the Advance Auto Supplies Store on Remount Road and Craig Streets in North Charleston during a traffic arrest. Scott was then allegedly shot eight times in the back to death by Officer Slager while Scott was running away. Slager was arrested for his actions after a local individual filmed the incident, which was then broadcast on television and social media. While it may be said that the arrest of Officer Slager prevented possible rioting that plagued other cities where such shootings have occurred, there were still angry protests that received far less attention from the mainstream media than the peaceful demonstrations, and when the Charleston Post and Courier attempted to interview North Charleston residents about complaints regarding local law enforcement, many refused to be quoted out of fear.

Two months later on June 17, nine local blacks including the church’s pastor were killed during a Bible Study at the historic Mother Emanuel AME Church in downtown Charleston. Again, the suspect was arrested. The international media focused on peaceful and harmonious demonstrations between the city’s racial and ethnic groups, but angrier nonviolent protests by more militant groups were again largely ignored.

The Role of Bernie Sanders

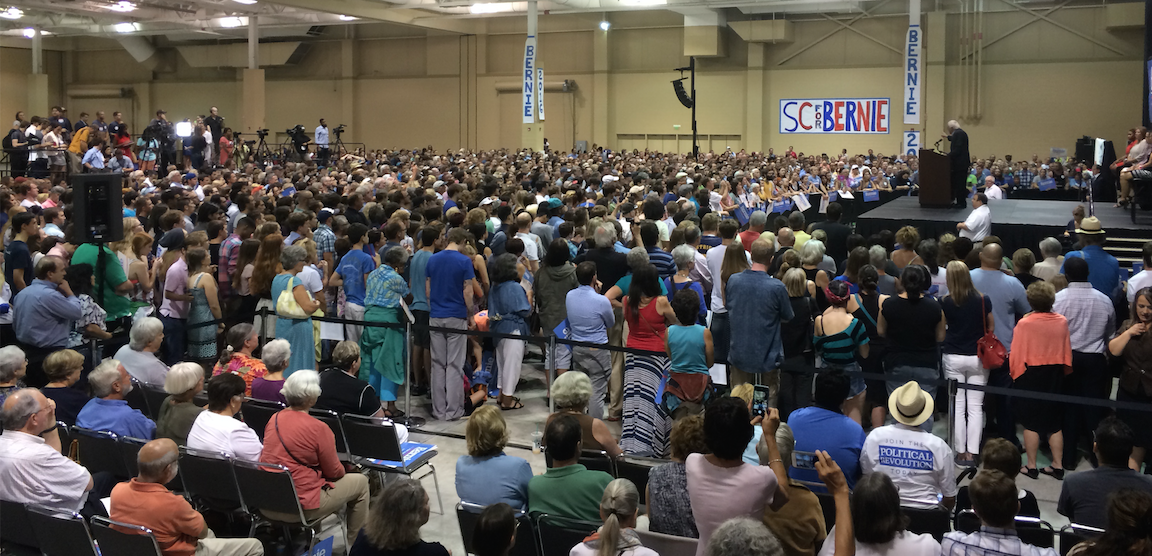

Sanders was scheduled to attend a rally in Charleston in June that was arranged before the Mother Emanuel shootings, but he cancelled this rally out of respect for the shooting victims. As it stands, while he is liked among the small community of black intellectuals and those who are not fond of the current Democratic front runner Hillary Clinton, he is not widely known among the black masses. While this was also true of current president Barack Obama in the early years of his campaign, President Obama had the advantage of inspiring racial pride among many blacks with his polished oratory and charisma.

While Bernie Sanders’ ideas tend to appeal to the small black intelligentsia, many politically active blacks remain supporters of the traditional Democratic Party and of Hillary Clinton. Unfortunately, many blacks in South Carolina are politically apathetic nonvoters (aside from being motivated to vote for President Obama in the last two presidential elections), and large numbers of men are disfranchised due to the felony restrictions put in place by the South Carolina “Jim Crow” Constitution of 1895, which remains in effect and continues in its original intention of reducing black voting power.

There is also the concern of the heckling by Sanders from two members of Black Lives Matter (a youth organization that grained prominence after a series of high profile killings of black youth by whites and policemen). While Black Lives Matter is still small in numbers on a national level as of this writing and their future remains to be seen, they are presently growing in influence and media attention, due largely to the lack of a coherent agenda of prominent traditional black leadership. As an emerging leader of the American left, Sanders would do well to engage in dialogue with its leadership.

While Sanders has recently published a position paper on race that covers such issues as police violence, disfranchisement, poor education, mass incarceration, affordable child care, and college costs, it needs additional input by black community members as well as the intelligentsia. The issue of gentrification and displacement, central to that of many blacks, needs to be covered, as well as the unique problems faced by rural blacks, who are ignored in policy discussions despite their large numbers (this is particularly true along South Carolina’s “Corridor of Shame,”-a poverty stricken black belt along Interstate 95 that was featured in the early days of the Obama campaign, but seldom heard from again, as well as the Mississippi Delta and the agrarian regions of other Southern states) must also be addressed.

Sanders must also make use of black media to reach out to this community. Appearances on radio programs with large black audiences such as Tom Joyner, Steve Harvey, and D.L. Hughley who are nationally syndicated are a must, along with black magazines as Ebony and Essence. Some inroads may also be considered among celebrities and music artists as well as ads in black newspapers. But while he is in Charleston, he would do well to travel throughout the black communities and listen to the common, everyday people to learn of their problems firsthand and unfiltered by officials and maintain contact and a relationship with these individuals if he is to succeed in preparing programs to gain the allegiance of the people.

Damon L. Fordham is a Charleston based author and historian.